Dr. Marilyn A. Brown, Regents and Brook Byers Professor

Climate and Energy Policy Lab

Georgia Institute of Technology

President Trump is pulling the United States out of the Paris climate change agreement, which calls on countries to limit global warming by reducing their greenhouse gas emissions. Marilyn Brown, the Brook Byers Professor of Sustainable Systems in the School of Public Policy at the Georgia Institute of Technology, explains the ramifications of Trump’s decision for the U.S. and the world and discusses the rise of the Carbon Dividend Plan.

With Existing Policies Plus the Carbon Dividend Plan

In 2016, the U.S. signed the Paris Accord, pledging to reduce its national greenhouse gas emissions by 26 percent to 28 percent below 2005 levels by 2025. Some analysts have suggested that the Accord would penalize the U.S. economy. This conclusion was emphasized by President Trump during his election campaign and in his press event announcing U.S. withdrawal.

But others have argued that participating in the Paris Accord would create jobs and grow the economy. It would provide a policy backbone for the U.S. clean tech industry to innovate and create new climate-friendly products like renewables, electric vehicles and energy-efficient equipment that could be exported to the rest of the world.

It is notable that companies like Wal-Mart, General Electric, Coca-Cola, and ExxonMobil have concluded that the Accord is good for business. At the same time, we continue to watch governors, state houses and mayors promote clean energy innovation, creating good-paying jobs while protecting our communities from pollution.

In place of the Obama administration’s Paris commitment and climate policies, the Trump administration is considering a Carbon Dividend Plan. Proposed by a newly formed Climate Leadership Council including Republican elder statesmen James A. Baker, Henry Paulson, and George P. Shultz, the plan calls for replacing the Obama administration’s climate policies with a rising carbon tax starting at $40 per ton. The tax would increase the cost of gasoline, electricity, and other carbon-emitting products, which would motivate producers and consumers to seek cleaner options. A carbon tax thereby fixes a major market flaw—the ability to freely emit damaging carbon pollution.

In return, carbon tax revenues would be given back to every American in the form of a quarterly check from the Social Security Administration. The idea is that increases in energy bills caused by the tax would be compensated by the tax dividends for most Americans.

Carbon taxes are being used today to tackle climate change in many countries around the world. For more than a decade, several northern European countries have had carbon taxes. In Canada, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has just set a minimum carbon tax of $10 per ton of CO2, and now China is introducing carbon taxes.

In all of these countries, carbon taxes are supplemented by other policies that motivate the shift to cleaner fuels and energy efficiency. Unpriced environmental “externalities” are not the only flaws impacting energy markets. Utilities with monopoly powers hinder competition and innovation. Landlords buy inefficient appliances for tenants who are stuck paying high power bills. Used car dealers sell “lemons” because unsuspecting buyers can’t tell the difference.

To address such market imperfections, the U.S. has implemented a portfolio of highly successful clean energy policies and programs including public-private science and technology partnerships, Energy Star labeling, model building codes, automobile and appliance standards, and the Better Bulidings Challenge.

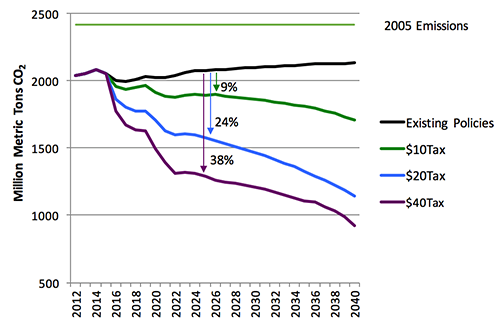

Georgia Tech’s Climate and Energy Policy Lab has modeled the impact of adding the Carbon Dividend Plan to today’s policies – focusing, in particular on how this would impact the electricity sector. With existing policies, CO2 emissions from the electricity industry are forecasted to rise slightly over the next quarter century. Emissions would decrease quickly if a $10, $20, or $40 carbon tax were added in 2020. In each case, we model a tax that rises by 5 percent each year, with revenues being returned to U.S. households.

With a $20 tax, CO2 emissions would drop by 24 percent below the forecasted level in 2025 and by 35 percent below U.S. emissions in 2005. This would exceed the U.S. national commitment to the Paris Accord. Thus, there would be room to dial back on some existing policies and programs that are judged to be inferior performers while building on the successes of outstanding programs.

This seems to me to be an effective and feasible bipartisan approach, and it could be achieved within the Paris Accord (thereby sustaining U.S. clean tech leadership), or it could be implemented outside of the Accord.